This past week, the resumption of the college football season brought a nation of fans and observers back in touch with the uniquely exasperating experiences that flow from the sport’s rule and policy structure… and its replay-booth reviewers. Lots of situations once again exposed various loopholes, inconsistencies, and overall deficiencies in the way the sport’s rules and replay policies are constructed. We’ll take you through five cases that are worth your attention:

*

THE CLOCK RESTART AFTER AN OFFENSIVE PENALTY IN THE FOURTH QUARTER

It’s always baffling… and it’s still in place: A team with a lead in the fourth quarter can commit a penalty, including delay of game, and yet receive the benefit of a restarted (counting) clock after the penalty. In Monday’s Louisville-Miami contest, the Cardinals, leading midway through the fourth quarter, committed a delay of game penalty at midfield. The clock was restarted, and Louisville had a chance to burn even more seconds than it actually did. The Cardinals snapped the ball with 13 seconds left on the play clock. As it was, they were able to drain at least 12 seconds off the game clock, maybe a few more.

It’s very simple: If an offensive team commits a penalty in the fourth quarter and has a lead, the clock should not be restarted after the penalty, especially if the penalty happens to be delay of game. At the very least, that can be made into an automatic rule. If that doesn’t strike you as fair, an alternative is that the defense can be given the choice of making the penalty a loss of down instead of a loss of five yards. (The former suggestion, mandating a clock stoppage, seems to be the simpler and fairer solution.)

*

TREATING FUMBLES DIFFERENTLY FROM CAUGHT PASSES

Last year, a new point of emphasis was introduced to the rulebook on the matter of pass receptions. I wrote about this tweak to the rulebook, essentially called the “Danny Coale Rule” in light of Coale’s disallowed catch at the end of Virginia Tech’s 2012 Sugar Bowl loss to Michigan. The basic point of this rule is that a ball can move around in the hands of a ballcarrier or receiver and still represent possession on the part of the player. Movement of a ball in a player’s hands does not constitute a loss of possession or the absence of possession.

The point of the “Danny Coale Rule” was to create necessary clarity in terms of the distinction between clasping the ball and not having a fundamental grip of the ball. A ball is either held by a player, or it is loose, genuinely separate from the player’s hands. This is why the rulebook was amended before the 2013 season, and the addition was a very welcome one.

Why, then, has replay not worked in concert with this point of emphasis on the matter of fumbles? Twice in week one, a player clearly had possession of the ball while being down (having a knee or elbow down, specifically). The ball was moving around in the player’s hand, but not to the point that it had been separated from the grip of the hand… not at the point when the knee or elbow was down. Yet, in both the Temple-Vanderbilt and Clemson-Georgia games, a fumble (by Vanderbilt and Georgia, respectively) was ruled to have occurred. Ball movement (not to be confused with “bowel movement,” though both of these rulings certainly seemed to stink…) was treated as a loss of possession.

That doesn’t seem fair or right to begin with, but it certainly cuts against recent — and enlightened — amendments to the rulebook. Pay attention to this tension point on future replays of a similar nature this year.

*

REVIEWING PASS INTERFERENCE:

SOMETHING THAT SHOULD HAVE BEEN DONE FIVE YEARS AGO

It’s long past time to make pass interference a reviewable play.

It’s true that Florida State received a lot of bad calls in its game against Oklahoma State on Saturday — let’s make that point quite clear. Yet, in a crucial moment, the Pokes were deprived of a first down on a third-and-nine play from the FSU 35. With Oklahoma State trailing by only three points, 20-17, midway through the third quarter, quarterback J.W. Walsh found Jhajuan Seales down the sideline. In real time, it seemed that Florida State’s P.J. Williams had broken up the play. ABC/ESPN analyst Kirk Herbstreit made the point that in real time, it was unreasonable to expect the official to call pass interference. Fair enough.

Yet, Herbstreit didn’t then make the obvious follow-up point: Replay was able to show that Williams interfered with Seales. This was and is exactly the kind of play a replay system can review to enable pass interference plays to be called correctly at a much higher rate. Everything about officiating and replay should exist in service of the need to correctly call as many plays as possible. Pass interference is one of football’s most consequential penalties, whether it’s called or not. Failing to make it reviewable remains one of the rule-and-policy structure’s greatest existing flaws.

*

THE NON-REVIEW PROBLEM: STILL IN EVIDENCE

It’s really rather absurd: Many fans will say that on Saturday in the Ohio State-Navy game, Buckeye head coach Urban Meyer deserved to be raked over the coals for not insisting on a replay review midway through the third quarter.

On a third-and-four play from Navy’s 48, Ezekiel Elliott appeared to have gotten a first down at the Navy 43. However, he lost the ball, which rolled to the 45, short of the first down. Officials conferred with each other for at least 15 seconds if not longer, giving the replay-booth reviewer plenty of time to realize that:

A) this was a multi-layered play which needed to be sorted out;

B) the officials were not sure of what happened and had to get their facts straight;

C) the reality of the play being a third-down play meant that the fate of this Ohio State possession rested very much on the ability of officials and the replay system to get this call right… which meant that a review of the play should have been a no-brainer.

Yet, this play was never reviewed. Replay angles provided by CBS Sports Network showed that Elliott had indeed gotten the first down at the 43, and that he was down before he fumbled. Yet, this play was never reviewed.

Meyer moved quickly on fourth down. Narrowly, this move did indeed reduce the amount of time the replay booth had to make a decision about whether or not to further examine the play. On that level, Meyer unquestionably goofed. Yet, if you were on #CollegeFootballTwitter at the time, it would have been easy for you to think that Meyer, not the replay-booth reviewer, committed the greater sin.

It’s really rather simple: A coach has a lot of different job descriptions. One of them is to be alert to the need to push for a replay review of important plays, but that’s something on which he needs help from assistants in the press box or other people with a clearer view of plays (this play occurred on the far side of the field, much closer to Navy’s sideline than Ohio State’s).

The replay-booth reviewer, on the other hand, has only one job. He (or she) does not have to worry about a fourth-down play and its personnel grouping. He doesn’t have to offer guidance to a young backup quarterback. He doesn’t have to mull over the play his offensive coordinator intends to select. The booth reviewer just has that one little responsibility: review the gull-darn play, especially when the ruling on the field (Elliott did not get a first down) deprives a team of the ability to comfortably continue its possession with a first down.

The reviewer committed the real sin here, while Meyer merely failed to correct it or point enough attention to it. Booth reviewers stealing paychecks is a problem that simply has to be expunged from the sport. A central command center would be a way to do this — if not nationally, certainly by conference. If the Big Ten had a replay command center, you can bet that this play would have been reviewed, as it should have been.

*

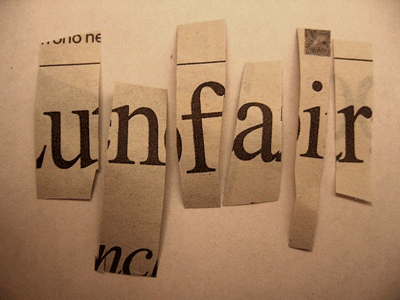

UNFAIR ACTS AND LOUISVILLE’S UNFORTUNATE MOMENT

The worst officiating episode from week one came on Monday night in the Louisville-Miami game.

Here’s the video of a backwards pass that was whistled dead as an incomplete pass by the officials on the field:

Check out this video #espn http://t.co/FMvceCpdPp

— Matt Zemek (@MattZemek) September 3, 2014

(If the screen says “Content Not Available,” don’t worry — you can still click the image and get the video to play.)

On this play from Miami-Louisville, the same problem re-emerged. Louisville and Miami players, as you can see in the video clip, both reacted to the play as though it was a fumble. Within that organic sequence, Louisville outhustled Miami and earned what had appeared to be a touchdown. Moreover, notice in the bottom right-hand corner of the screen the official running to keep pace with the play. Even though a whistle was blown (to rule the play an incomplete pass), the other officials didn’t stop their own actions, which is a common if not universal response to a dead-ball ruling.

Any common-sense position would allow Louisville to be given a touchdown there.

Who said college football’s rule-and-policy structure is largely based on common sense?

The rulebook says the following on page FR-107 — Rule 12, Section 3, Article 3, item d:

“Loose ball ruled dead, or live ball ruled dead in possession of a ball carrier

when the clear recovery of a loose ball occurs in the immediate continuing

action.

1. If the ball is ruled dead and the replay official does not have indisputable

video evidence as to which team recovers, the dead-ball ruling stands.

2. If the replay official rules that the ball was not dead, it belongs to the

recovering team at the spot of the recovery and any advance is nullified.”

In discussing the play with ESPN rules expert and former Pac-12 official Dave Cutaia, I was informed that the rulebook does have a provision in which officials can allow a touchdown for certain unforeseen incidents. This subsection is titled “Unfair Acts” in the rulebook, and it’s found on pages FR-94 and FR-95, in Rule 9, Section 2, Article 3:

“The following are unfair acts:

a. While the ball is alive and during the continuing action after the ball has

been declared dead, any person other than a player or an official interferes

in any way with the ball, player or an official.

b. A team refuses to play within two minutes after ordered to do so by the

referee.

c. A team repeatedly commits fouls for which penalties can be enforced only

by halving the distance to its goal line.

d. An obviously unfair act not specifically covered by the rules occurs during

the game (A.R. 4-2-1-II and 9-2-3-I).

PENALTY—The referee may take any action he considers equitable,

which includes directing that the down be repeated, including

assessing a 15-yard penalty, awarding a score, or suspending or

forfeiting the game [S27].”

Why, then, wasn’t Louisville given a touchdown? This was an unfair act, right? This was under the discretion or purview of the officials to grant the touchdown to Louisville, yes?

Well, the explanation here is that the above “unfair acts” pertain to unsportsmanlike acts, generally on the part of players. Think of Alabama’s Tommy Lewis coming off the sideline to tackle Rice’s Dicky Meagle in the 1954 Cotton Bowl:

That’s viewed as an unfair act.

Louisville getting jobbed by the rulebook? Well, that’s not “unfair” enough, apparently.

Welcome back to college football’s rule-and-policy structure, folks. Ain’t it grand?