What’s the greatest college football dynasty of all time?

That’s a question which deserves to be explored, and it will be in the paragraphs below, but don’t think the answer is an easy or obvious one. That does a disservice to the notion of a dynasty in an age when attention spans are shorter.

It’s easy to ask about the best dynasty of all time. It’s harder to get at this question: Is a dynasty really a dynasty if it applies to no more than four seasons? The royals in England; the rulers of China through the centuries; the Medicis in Italy; the hegemony of the Habsburgs — these were not five-year tastes of power, to say the least. It’s reasonable for a critic to contend that a true dynasty needs to be longer than half a decade.

Yet, that’s not the only voice in the room. Plenty of people will readily identify, in other sports, the New England Patriots of 2001-2004; the Los Angeles Lakers of 2000-2002; the New York Islanders of 1980-1983; and other similar examples across the spectrum, as genuine dynasties. If you were to ask a group of 100 sports fans about the parameters and qualifications of a “dynasty,” you’d probably get an overwhelming majority to agree that the above examples from various sports deserve to be seen as dynasties.

Why is this the case?

This is what we’ll explore in a survey of college football dynasties through the years.

*

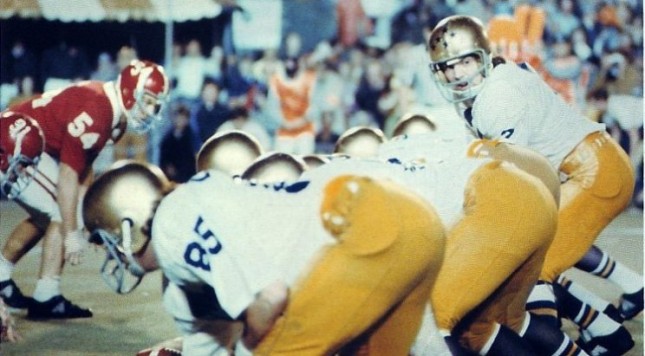

THE FIRST GREAT COLLEGE FOOTBALL DYNASTIES: PRINCETON AND YALE

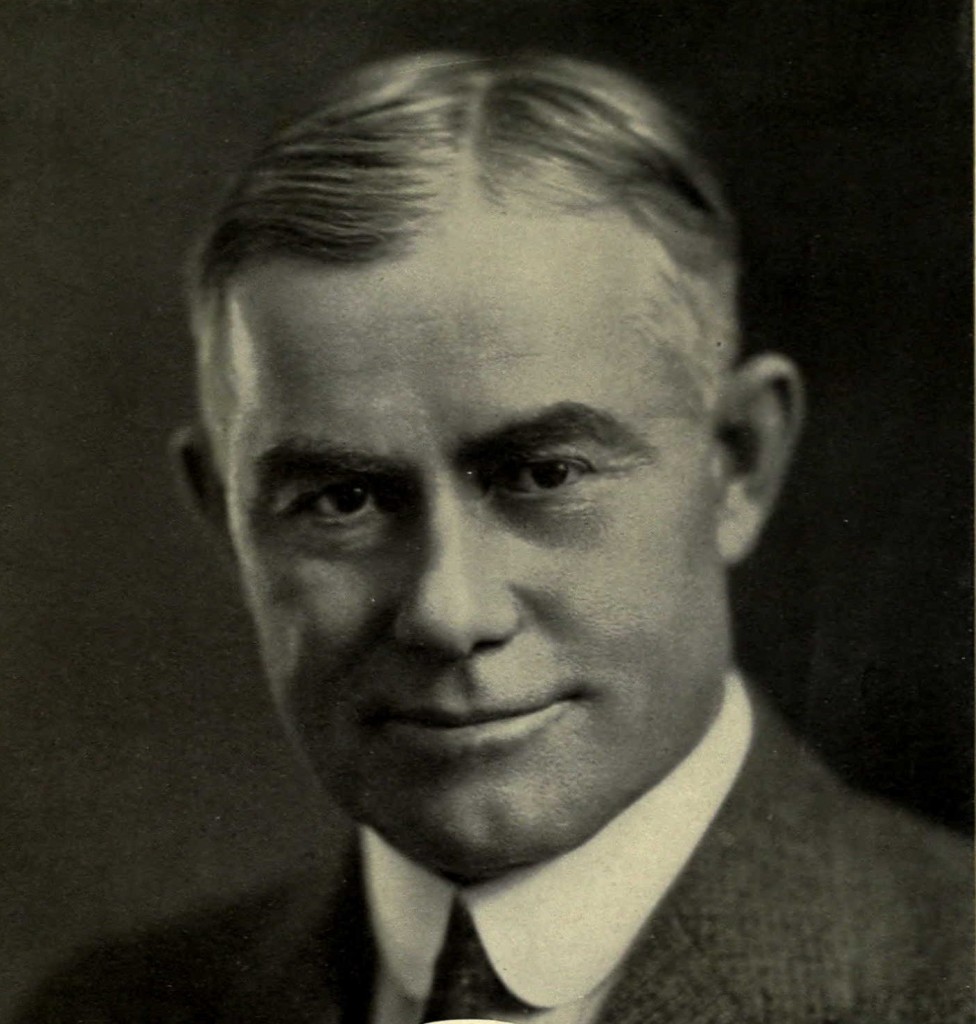

Walter Camp, former coach of the Yale Bulldogs, is called “The Father of Football,” due to the fact that he created many of the foundational rules and structures that gave the sport its present-day shape. Since Camp helped develop the modern game, it’s reasonable to argue that Yale is the first true dynasty in the sport, even though Princeton was the premier team of the 1870s, the first full calendar decade in which college football was played.

Most fans with more than just a passing or casual interest in college football know that the first college football game was played in 1869 between Princeton and Rutgers. Princeton was the best team of the 1870s, but in that decade, seasons didn’t constitute more than a handful of games, as you can see here if you scroll all the way to the bottom of the chart. Before Michigan came along under Fielding Yost in 1901, college football supremacy belonged to the Ivy League. During these years, if either Princeton or Yale lost more than one game in a season, it rated as both an aberration and a massive shock.

Yale, under coach Walter Camp, went 68-2 in a five-season span from 1888 through 1892. The program, led by other coaches in subsequent years, lost only 12 games in 22 seasons, from 1888 through 1909. Princeton, in a run beginning in 1884, lost only 12 games in a 16-season run that concluded in 1899. Harvard was merely the third-best Ivy League team of the era… which meant it was still excellent in its own right. The Crimson produced a smaller run of dominance in the early 1890s — 46-3 from 1890 through 1893 — and then a tremendous eight-season stretch from 1908 through 1915, losing only four times in those years. Beginning in 1894, which was “late” by Ivy League standards, Pennsylvania took off and became a powerful and more prominent team in the conference. From 1894 through 1898, the Quakers compiled a 67-2 record (playing 14 or more games in seasons when many other teams didn’t do the same; still, the feat remains impressive).

The Ivy League gave up Division I football after the 1981 season, but its place in college football’s early history is part of a larger dynastic narrative.

*

BRAND-NAME EARLY-PERIOD DYNASTIES

Fielding Yost put Michigan football on the map, establishing one of the most stable college football programs in the United States. The blundering ways of Michigan athletic director David Brandon stand in such marked contrast to the smooth, reliable continuity provided by Bo Schembechler and Lloyd Carr… continuity first set in motion by Yost, the winner of the first Rose Bowl game in 1902.

The Rose Bowl is college football’s greatest and most cherished single-game event. Fielding Yost’s first Michigan team won it, 49-0, over Stanford. The greatness of Yost and the Michigan dynasty he helped create in the first quarter of the 20th century can be found in this pair of facts: Yost lost once in his first five seasons on the job (1901-1905) and only thrice in his final five seasons on the job, concluding in 1926. When one thinks of the label “champions of the West” in “Hail to the Victors,” the line seems so discordant in a context of current American geography. Yet, when you realize that the Ivies owned college football until Yost came along, the truly “Western” nature of Michigan’s ascendancy becomes real and that much more understandable. What we know today as the Big Ten was then the Western Conference, anyway, making “champions of the West” a precise and factual reference, not some airy and pretentious boast.

Knute Rockne made Notre Dame football with his charisma and leadership… and by hardly ever losing football games, which makes charisma matter more in the mind’s eye of recollection.

Michigan, thanks to what Yost began, is one of the three winningest FBS programs of all time. Notre Dame is also in that top three, and the man who did in South Bend what Yost forged in Ann Arbor is Knute Rockne. Yes, predecessor Jesse Harper certainly laid the foundation for Rockne, but someone needed to carry along the Fighting Irish with a prolonged tenure that would cement the program’s presence on a national level. Rockne became that man, leading the Irish to the Rose Bowl in the seminal 1925 game against Stanford. It was Rockne’s teams who were written about by Grantland Rice, giving rise to the Four Horsemen and a mythic aura that captured the nation’s imagination. Rockne stands at the center of college football’s story. He is one of a few key figures — Red Grange of Illinois being another — who made the sport popular on a larger level and catapulted it through the first half of the century, giving it the legs needed to then settle into a more regional identity as conferences grew and became more established (and organized) in the 1950s and beyond.

How great was Rockne as a coach? He guided Notre Dame for 13 seasons before being killed in a plane crash in 1931. In those 13 seasons, Notre Dame lost more than two games in one season, and more than once in only two seasons. The years 1925 through 1928 (28-8-1) were comparatively bumpy when measured against Rockne’s 1919-1924 prosperity (55-3-1), but Notre Dame under Rockne unquestionably qualifies as a dynasty, primarily because of the longevity attached to the quality. The most recognizable dynasties are the ones that endured, and when looking at the first third of the 20th century, Michigan under Yost and Notre Dame under Rockne lead the pack.

*

OTHER UNQUESTIONED DYNASTIES THROUGH THE YEARS

Everybody knows that under Bud Wilkinson, Oklahoma won 47 straight games, bridging the 1953 through 1957 seasons. Yet, what gets lost in that run of excellence is that from 1948 through 1952, the Sooners lost only five times as well.

In subsequent decades, other dynasties made themselves plain precisely because they lasted a lot more than half a decade. Oklahoma, under Bud Wilkinson, lost a total of eight games in an 11-season stretch from 1948 through 1958.

Army, under Red Blaik, lost only three games in a seven-season stretch from 1944 through 1950.

When Rockne’s career at Notre Dame ended (because his life tragically ended well before its time), Howard Jones set in motion a seven-year period of brilliance at Southern California. The USC Trojans lost seven games from 1927 through 1933, making and winning three Rose Bowls during that stretch.

*

Enough about the middle third of the 20th century, though. In the final third of the century, several more schools announced themselves as dynasties.

The desire to learn, and the ability to make substantial changes midway through a career, offer a glimpse of the competitive qualities that made Paul “Bear” Bryant who he was as a coach… and established Alabama as the most accomplished program in college football during his tenure, with five Associated Press national championships.

Alabama had actually emerged as a powerhouse by losing only five times in a six-season span from 1961 through 1966, but it was in the 1970s when Bear Bryant truly made himself one of the greatest coaches in the sport’s history, alongside Rockne and a few select others. After a period of stagnation in the late 1960s, Bryant learned the wishbone offense from his friend Darrell Royal at Texas. He felt the need to change the way his team played, not an easy decision for someone who had ruled the sport for half a decade. (Think of Steve Spurrier adopting a more run-based approach at South Carolina, also adjusting to the times in which he coached.) Bryant wasn’t only willing to learn, though; he was able to put his knowledge to good use. Alabama lost more than two games in a season only once from 1971 through 1979. The ’79 team was one of the more dominant teams in the sport’s history. Bryant got better as he aged; the 1970s were even better than the 1960s for the Bear, and the ’60s were pretty good.

Penn State lost only eight times in a seven-season period from 1968 through 1974. Joe Paterno’s best feat as Penn State’s coach was arguably his ability to produce five unbeaten seasons. Even after periods of comparative struggle, Paterno would emerge from the pack and come up with a masterpiece of a season every now and then (1973, 1986, 1994). However, it was in the late 1960s when his program found the consistency that would entrench the Nittany Lions as one of college football’s foremost powers. From 1968 through 1982 and then again throughout the 1990s (1990-1999), Penn State became a program that hardly ever missed a chance to achieve at a relatively high level.

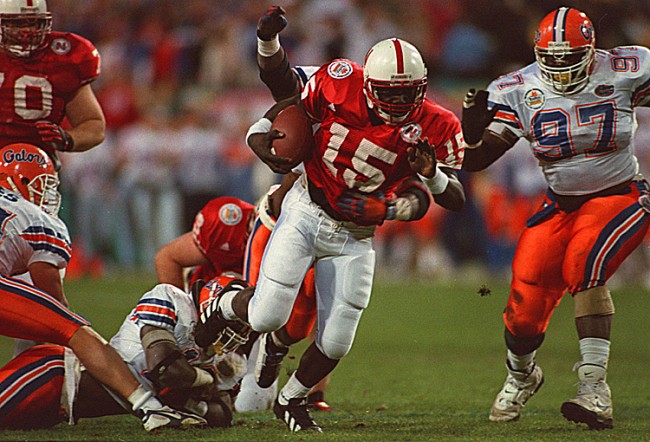

Also in the 1970s, Oklahoma and Nebraska became Heartland heavyweights. Oklahoma lost only three times from 1971 through 1975 and lost only nine times in nine seasons, from 1971 through 1979. Nebraska pulled off two straight unbeaten seasons in 1970 and 1971, the centerpieces of a prolonged period of relentlessly high-level success in which a 9-3 season was the absolute floor for the Cornhuskers. From 1969 through 1997, Nebraska never lost more than three games in a season. From ’69 through 2001, the program lost more than three games in a season only once (1998).

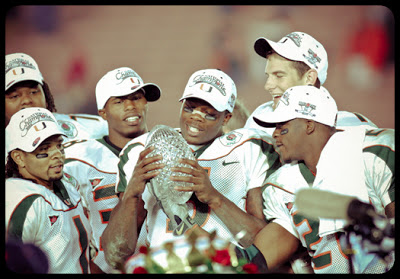

The other three foremost dynasties — the ones that, like every other dynasty previously mentioned here, make the cut without any debate whatsoever — all hail from the state of Florida.

Miami, especially from 1985 through 1992, put its boot on the throat of almost every foe it faced. The Hurricanes lost just eight games in those eight seasons. In 1985 and 1990, the Hurricanes lost two games, meaning that in the other six seasons from that eight-year run, The U surrendered only four defeats. It took all-time-great performances on at least one side of the ball, if not both, to deny the Canes the national title.

Florida, under Steve Spurrier from 1990 through 1996, either won the SEC or (in recognition of the 1990 season) finished first in the SEC standings six times, missing out only in 1992 (Alabama). Florida exceeded the “more than just five years” standard that makes a dynasty clear-cut by just about any measurement.

Yet, as good as Spurrier was in Gainesville, his career would have been so much better if not for the next dynasty on this list, perhaps the greatest in college football history if you adjust for circumstances:

Florida State’s 14-season run, from 1987 through 2000, will long be regarded by college football historians as one of the most spectacular “how’d he do that?” achievements in the sport’s existence.

Spurrier never did win a game in Doak Campbell Stadium. That’s because Bobby Bowden always found a way to outfox the Swamp Fox. Bowden’s achievements are magnified by the fact that he essentially built Florida State from nothing; it’s not as though this was an established school when Bowden moved to Tallahassee from his previous stop at West Virginia.

The central achievement at the heart of Florida State’s greatness — the cornerstone of Bowden’s legacy as a head coach — is that for 14 straight seasons, the Seminoles finished in the top five in the national polls (and in the top four for 13 straight seasons; FSU finished No. 5 in 2000, when the Seminoles reached the national title game but mysteriously fell to fifth after losing to Oklahoma).

It’s the kind of record which — like Roger Federer’s 23 straight major singles semifinal appearances or Cal Ripken’s consecutive games played streak — isn’t going to be matched anytime soon. It’s going to be that sparkling diamond of an achievement that will never ever dim as the decades pass along. Florida State, when seen through the prism of top-quality longevity, just might be the best dynasty of modern times in college football.

This leads us to the final section of our study.

*

THE TRUE DEBATE: HOW LONG CAN A DYNASTY BE SAID TO LAST?

The 2001 Miami Hurricanes and the 1995 Nebraska Cornhuskers, both pictured above, are the two greatest teams any college football fan or pundit under 40 years of age has been able to witness with his or her own eyes. This is not a unanimous point — someone might regard the 2004 USC team or the 1991 Washington team or the 1987 Miami team as the best — but it’s assuredly a majority opinion. The 2001 Canes and the 1995 Huskers were the best teams in three-to-five-year stretches for those programs. Miami, from 2000-2003, attained an uncommon level of excellence; Nebraska, from 1993 through 1997, did the same. These programs and a few others through the decades have managed to rise to unfathomable heights in half a decade or less… but the enormity of their achievements simply could not be sustained for a longer period of time.

Some examples:

Notre Dame, from 1946 through 1949 under Frank Leahy, did not lose a game. The Irish then lost eight games the following three seasons from 1950 through 1952.

USC, under John McKay, went 29-2-2 from 1967 through 1969; then lost four games in each of the next two seasons; then went 31-3-2 from 1972 through 1974; and lost four games in 1975.

Texas, under Darrell Royal, lost only three games from 1961 through 1964; then lost 12 games the next three seasons; and then lost only twice in a three-season span from 1968 through 1970.

Minnesota won three AP national titles from 1936 through 1941, but the Golden Gophers lost eight games in three ordinary seasons from 1937 through 1939. (A point of clarification here: The AP poll’s first season was in 1936. Had it existed in 1934, Minnesota might have won two additional AP titles. The Gophers rate as a dynasty, but it’s worth using that shorter time block from 1936-’41 as an example of a few brilliant seasons existing in a small cluster, interrupted or bracketed by ordinary seasons.)

Urban Meyer produced three spectacular seasons at Florida from 2006 through 2009. The Gators were a top power in the sport, but their post-Spurrier reign didn’t last as long. Is that a dynasty? Do you call a three-to-five-season period a dynasty, as is the case in the above examples?

It’s perfectly reasonable to say yes… and it’s also reasonable to say no.

*

Let’s now go back to the question brought up at the beginning of this piece, in order to bring our journey to — if not a conclusion — a point that you can discuss with your college football-loving friends: Is a dynasty really a dynasty if it applies to no more than four (or, heck, five) seasons?

In this modern age, the media scrutiny devoted to even one season is so witheringly intense. The ways in which human beings process an ever more abundant supply of opinion, commentary, statistical analysis, and behind-the-scenes intrigues are so layered and constant. The weight of a season and the pressures attached to it are so substantial — or at least, they feel that way — that being able to win two straight national titles or three in four years can make it seem as though a given program owns a permanent presence on the landscape. This is what has marked Alabama as the team of teams in college football since the 2009 season. (What’s also true is that teams played at least 14 games en route to recent BCS-era national titles. Teams in past decades played as few as eight in the case of 1930s-era Minnesota, and 10 in the case of 1950s-era Oklahoma.)

Yet, Alabama’s critics will point out that the Crimson Tide have won the SEC championship only twice in the past five seasons, only once since 2010 (with Auburn winning more SEC titles over the past four seasons). No one would identify Auburn as dynastic, and yet the Tigers have more SEC crowns than big, bad Bama over the last four seasons. This kind of cluttered dynamic certainly gives one reason to think about the parameters we assign to dynasties, the ground rules we establish in our own minds. It’s not as though there’s a “Dynasty Handbook” on the shelf somewhere in Bristol, Connecticut, or in CBS studios in New York, or at the College Football Hall of Fame in Atlanta.

Yes, if you’re asking me, teams that soar to incredible heights in a three- or four-year span in college football or other sports SHOULD be viewed as dynasties. Yet, I’ll just as readily acknowledge that such a statement is confined to the province of opinion, not fact.

Dynasties do come in various shapes and sizes. Toledo, after all, won 35 games in a row from 1969 through 1971. Am I going to say the Rockets are not a dynasty? No.

It’s up to you to draw the lines yourself… and that’s the eternally fun aspect of this always-fascinating topic.