Roughly 90 years ago, the Alabama Crimson Tide established themselves as the signature program of the Southern United States.

Today, a second straight appearance in the College Football playoff — following three BCS national championships and a full-fledged revival of the program under Nick Saban — has reaffirmed Alabama’s place as the South’s ultimate program… and college football’s foremost colossus.

What happened 90 years ago and what exists today are knitted together by another event which occurred in the middle of the vast ocean Tide of college football history. Verily, 45 years after Alabama became a national name, and 45 years before today’s team returned to the College Football Playoff, the Crimson Tide participated in a game which transformed both the program itself and college football as a whole.

The beginning and the metamorphosis of Alabama football are well worth celebrating, as the Crimson Tide remind everyone that they’re the most successful program college football has ever known.

*

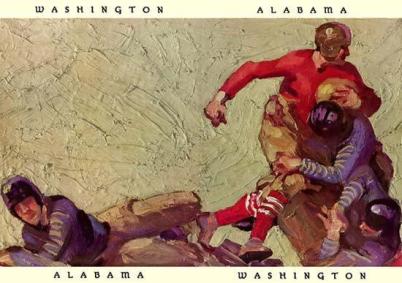

To understand the importance of the 1925 Alabama team and its 1926 Rose Bowl game against Washington, this video offers a perfectly good primer:

The basic facts are worth mentioning in brief:

Entering the 1925 season, no Southern team had ever played in the Rose Bowl. Being given an invitation to the 1926 game represented a high honor for Alabama, but also for all Southern schools. From a non-Southern perspective, it is possible to intellectually comprehend and process the importance of Alabama going to the Rose Bowl in the 1925 season, but it’s impossible to fully understand the magnitude of the moment on emotional and spiritual levels.

For Southerners emerging from the rubble of Reconstruction and all the devastatation — material and psychological — visited upon the region in that era of American history, the 1926 Rose Bowl was not just Alabama’s moment; it was a Southern moment, a “we” moment.

When Super Bowl III occurred between the New York Jets and the Baltimore Colts, the Jets were carrying the banner of the American Football League against the old-guard NFL. That, however, was merely the fight of a professional sports league, a business. The 1926 Rose Bowl was about the soul of a region which lacked the urban manufacturing infrastructure of the American Northeast. College football — with its more localized, nativist passions — was intended to be the pursuit in which the South could exceed the North. This was a way in which a wounded and battered region could feel good about itself again.

The 1926 Rose Bowl invitation to Alabama conferred upon the Tide an enormous amount of responsibility. It’s hard enough to appreciate this reality nearly 90 years to the day of the game (January 1, 1926), and it’s even more difficult to absorb the situation from a non-Southern perspective.

Notice the subhead from the New York Times clipping above.

Alabama didn’t merely beat Washington, 20-19, on that afternoon in the Arroyo Seco. The Crimson Tide and head coach Wallace Wade (who later made Duke a national power on the gridiron) didn’t merely complete an unbeaten season in which they allowed only one touchdown preceding their trip to Pasadena. Alabama put the South on the college football map, forcing the rest of the nation to pay attention to the region which had struggled over the preceding 60 years.

In light of the 1926 Rose Bowl’s connection to the South’s rise from Reconstruction and the scars of the Civil War, how utterly fascinating it is that the other supremely important game in Alabama football history marked a different kind of reconstruction, a transition from a previous and pervasive way of being.

*

Alabama — built by Wallace Wade and his successor, Frank Thomas — went through a lull in the mid-1950s before hiring Paul W. Bryant as its next head coach after the 1957 season. The Bear turned the Tide in Tuscaloosa, reviving Alabama as a top-tier national power over the next decade. However, at the very end of the 1960s, Alabama lost steam. On one level, the Tide’s offense became more predictable. Bryant consulted his friend Darrell Royal at Texas to learn about the wishbone offense, and the switch to that offense enabled Bama to become bigger and better than ever in the 1970s.

However, one other change played an even more fundamental role in restoring the Crimson Tide during Bryant’s unfathomably successful tenure.

The seeds of that transformation were planted by other teams and schools, such as Michigan State, Kentucky, and Tennessee, in the latter half of the 1960s. The trees of integration in college football grew on the night of September 12, 1970.

It’s true that the wheels of integration — the recruitment of African-American college football players — were already turning in the second half of the 1960s, thanks to what Duffy Daugherty had done at Michigan State, and due to what the University of Kentucky had achieved in bringing aboard Nat Northington and Greg Page.

Yet, small beginnings and tentative steps need to give way to a more massive, wide-scale movement. Initial stirrings in the pursuit of a far greater goal all require that tipping point when everyone in the room sees the value of a practice beyond any reasonable doubt.

That tipping point was provided by the University of Southern California and fullback Sam Cunningham, who strode into Birmingham’s Legion Field and thumped Alabama, 42-21.

The fact that USC defeated Alabama wasn’t the headline-grabbing development of the night. The how of the Trojans’ win — chiefly, the players who primarily authored the conquest — left an everlasting mark on college football, convincing the man widely regarded as the sport’s greatest coach that he needed to drastically reorder his entire recruiting approach.

Indeed, this wasn’t merely about USC winning and Alabama losing. Several specific details made this game the change agent it ultimately became.

For one thing, USC had established itself as a school with outstanding African-American players, especially at the running back position. Mike Garrett won the Heisman Trophy in 1965. Three years later, Orenthal James Simpson — yes, O.J. — won the 1968 stiff-arm trophy. The 1970 USC team was the first fully integrated team to play in Alabama. The Trojans had an all-black backfield — not just Sam Cunningham at fullback, but quarterback Jimmy Jones and a running back named Clarence Davis.

A moderately important note about Davis (to put it mildly): He was born in the very city where that USC-Alabama game was played. The Birmingham native left the South to play college football elsewhere.

Yes, a few African-American players had already been recruited, or were in the process of being recruited — even by The Bear at Alabama — before USC demolished the Tide on that night in 1970. Yet, for all the myths and falsehoods attached to this game and the events which surrounded it, this much is true: USC 42, Alabama 21, clearly accelerated the rate at which African-American players were brought into Southern programs.

Jones, at quarterback, presided over a magnificent performance from the USC offense. Davis, playing in his birthplace, collected 76 yards on 13 carries — nearly six yards a crack — and hauled in a 23-yard touchdown pass from Jones. Cunningham (pictured below) ripped through Alabama’s defense for 135 yards on just 12 carries.

This was about USC’s all-black backfield. This was about the Trojans showing levels of speed and power Alabama could not match. This was about Alabama not yet having the wishbone offense which would avenge this loss a year later in 1971 in Los Angeles, catapulting The Bear and the Tide back to national prominence.

September 12, 1970, gathered all those tension points and more, changing the ways in which college football players were recruited on a mass scale.

*

The 1925 season. The 1970 season. The 2015 season.

Ancient times. A more recent yesterday. The present moment.

Three periods in college football history, neatly separated by 45 years apiece.

The Alabama of today owes its prominence to Saban and the players whose hard work has paid off so handsomely. Yet, the Crimson Tide would not have achieved such enduring centrality in college football had it not been for the 1925 team which won the school’s first Rose Bowl and made the South feel it could achieve on a national scope in this sport. Alabama wouldn’t be where it is today had the program not emerged from its “Old South” shell and a longstanding way of doing things, shaken into modernity by USC in 1970.

The 1926 Rose Bowl instilled and affirmed a set of beliefs.

The 1970 USC game decisively and powerfully altered them.

Alabama will play one of the biggest games in school history in the upcoming College Football Playoff semifinals against Michigan State. That much is true. However, when identifying the two most significant games in the history of the Crimson Tide, the 1926 Rose Bowl and the 1970 USC game stand above all others. Once in victory and once in defeat, Alabama created two moments which forever changed college football.