When the 2015 Iowa Hawkeyes take the field for the Rose Bowl game this Friday, they’ll certainly attempt to win for themselves, to achieve something in the present moment.

Yet, as much as every competition is about the opponent and the opportunity in front of one’s nose, some games have a way of reaching more deeply into a community’s history. Such is the case for Iowa when it plays the Stanford Cardinal in college football’s most famous postseason setting.

*

Yes, Iowa wants to validate its 2015 season. The Hawkeyes want to beat a highly credentialed Stanford program which has won three Pac-12 titles in four seasons, and has reached five New Year’s Day bowls in the past six seasons. A victory over the Trees near the San Gabriel Mountains would silence a lot of the chatter about Iowa’s lack of legitimacy this season. The Hawkeyes would prove themselves beyond any and all remaining doubt. That’s a lot to play for within the context of today.

Yet, Iowa is playing to reconcile a state and a program with its yesterdays.

The Hawkeyes will take the field with a childlike joy familiar to past generations of fans, but if they leave the Rose Bowl stadium without a trophy, the experiences of the 1980s will be acutely — painfully — real once again.

*

There’s a certain kind of agony attached to Iowa’s Rose Bowl history. The Hawkeyes forged unbeaten seasons in 1921 and 1922 under Howard Jones, but at that time in college football, the Rose Bowl — just trying to find its footing — invited teams across the United States to play the Pacific Coast Conference (later Pac-8, then Pac-10, now Pac-12) champion. From 1916 through 1946, only one Big Ten (formerly Western Conference) school went to the Rose Bowl. That was Ohio State in 1921, after the 1920 season. Iowa’s two unbeaten seasons just after OSU’s invitation were not rewarded with a trip to Southern California. That’s rotten luck, but that has been Iowa’s relationship with the Rose Bowl for all but a few years.

The sting of irony became more pronounced for Iowa when Jones left for USC and made five Rose Bowls with the Trojans. If Jones left Iowa so he could play in more Rose Bowls in Los Angeles with the Men of Troy, his decision was entirely the right one. Nevertheless, Iowa had still not made a Rose Bowl as the decades flew by and the wars of the 20th century came and went.

World War II ran its course. Then came the Korean War. Iowa entered the early 1950s without a Rose Bowl appearance, even as the Big Ten finally began its longstanding relationship with the event in 1947.

It was only then that the Hawkeyes began to sip from the cup of happiness.

*

The man who transformed Iowa’s relationship with the Rose Bowl was Forest Evashevski. He needed a few years to find his footing in Iowa City, but once he figured out the right way to go about his business, he didn’t relent. Whereas Howard Jones never got the chance to lead Iowa into the Rose Bowl, Evashevski guided the Hawkeyes to the hilltop on the first day of 1957. Following a brilliant 1956 regular season, Iowa played Oregon State in an outsider’s Rose Bowl and won that game to achieve a piece of gridiron immortality.

The question immediately confronted Evashevski and his team: Would it be known as a one-hit wonder, a team which claimed a single moment in time, or would it build upon a shining success and flourish even as it became a target in the Big Ten?

The Hawkeyes authoritatively answered that question the way they wanted to.

Iowa’s teams under Evashevski lost just one game per season in three of the next four years, 1959 being the exception. Iowa became a rock of reliability, a program which had finally captured a previously elusive formula for success.

Having produced a Rose Bowl season in 1956, crowned by its victory on New Year’s Day of 1957, the Hawkeyes validated their emergence by making the journey all over again two years later.

Iowa earned its ticket to Southern California with a superb 1958 season. The Hawkeyes stepped inside the Rose Bowl stadium again on the first day of 1959. Once more, the opponent was not one of the West Coast’s foremost powers. Once more, Iowa thumped that foe, drubbing California and reasserting itself as one of the best programs in the latter half of the 1950s. (As a side note, California has never returned to the Rose Bowl over the past 57 years. It’s the longest Rose Bowl drought of any original Pac-8 school. Minnesota has the longest drought of any original Big Ten or Western Conference school.)

When the 1960 college football season ended, Iowa was ranked third in the nation. The Hawkeyes were then installed as the preseason No. 1 team in 1961. The future promised more and more riches for Iowa football.

The future’s promises turned out to be empty.

A few changes lay at the heart of why the Hawkeyes couldn’t continue to thrive: the coach; the athletic director; and the culture in and around Iowa’s athletic department. Those three changes all revolved around the same man.

Evashevski — done with coaching before turning 43 years old — moved to the AD chair in Iowa City. Assistant coach Jerry Burns, whom some of you might remember as the coach of the Minnesota Vikings in the late 1980s (who barely missed the Super Bowl in the 1987 season), took over. However, Evashevski simply wasn’t a good athletic director. He didn’t give Burns a climate in which he could excel. Recruiting tailed off, and the Hawkeyes lost their way. Evashevski — such a powerful and widely respected figure when he stepped down as head coach in late 1960 — left behind a very different legacy as an administrator when he was ousted as athletic director in 1970.

Because of the lost decade Iowa experienced in the 1960s, the program struggled to gain traction in the 1970s, with Woody Hayes and Bo Schembechler in the middle of their Ten-Year War at Ohio State and Michigan. In 1979, the school selected Hayden Fry — a Texan who was moderately but not overwhelmingly successful at SMU and North Texas — to resurrect the Evashevski years. It was hard to be too optimistic at the time about Iowa’s future.

In two short years, the gray skies which had blanketed Iowa City gave way to a gleaming new sunshine created by the bright minds Fry brought onto his coaching staff.

*

Hayden Fry planted one of the great coaching trees in college football history.

Bill Snyder was his offensive coordinator. Barry Alvarez coached the linebackers. Dan McCarney coached the defensive line.

In 1981, an offensive line coach joined Fry’s army of elite assistants. The name? Kirk Ferentz.

Did Ferentz’s presence put Iowa over the top? Probably not. Yet, that 1981 Iowa coaching staff rates as one of the best ever assembled. The talent on the sidelines and the talent on the field formed a magical combination, one which lifted the Hawkeyes to the Big Ten championship and the 1982 Rose Bowl against Washington. If Evashevski led Iowa out of the Forest in 1956, Fry led Iowa out of the darkness and into the California light in 1981. After more than 20 years of walking in the wilderness, the Hawkeyes had returned to the center of the college football conversation.

What’s better is that they stayed there for another decade, creating the quality longevity which eluded the program at the start of the 1960s.

Iowa returned to the Rose Bowl in the 1985 and 1990 seasons while winning 10 games in two other non-Granddaddy years (1987 and 1991). With his best assistants still in the fold, Fry was able to maintain what he built. It was once again a great time to be a Hawkeye.

There was just one problem: Whereas Evashevski won his two Rose Bowls in the 1950s, Fry and Iowa went 0 for 3 in Pasadena.

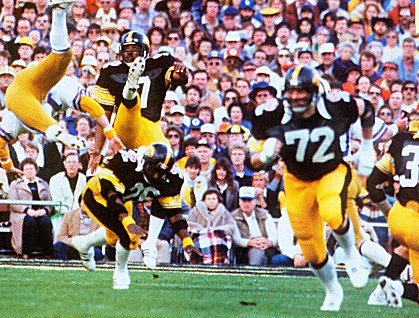

The Hawkeyes’ story in their Hayden Fry Rose Bowl trips is embodied in the cover photo above. The Hawks were nothing if not tough — you can see a Washington Husky player thrown into the air by a devastating block. However, a Reggie Roby punt was as much of a highlight as the Hawkeyes generated in the 1982 Rose Bowl, their return to the national limelight.

Roby led the nation with a jawdropping 49.8-yard-per-punt average in the 1981 season, but with very few exceptions, a punter doesn’t want to be known as his team’s foremost player in a big game. A weather-dominated 9-6 slugfest? Perhaps that’s when a punter really can be a game’s MVP. On January 1, 1982, Washington and Jacque Robinson had too much playmaking speed and skill for Iowa to be able to win a slobberknocker special.

It’s a simplistic summation of Iowa’s three trips to Pasadena from 1982 through 1991, but it’s not inaccurate: Pac-10 teams with speed — both on the edges and through gaps — were able to catch Iowa off guard. It’s not as though Iowa was unique in this respect: From 1975 through 1987, Michigan — in 1981 — gave the Big Ten its only Rose Bowl win over the Pac-8/10. Nevertheless, Iowa suffered as a result. Great seasons and formidable accomplishments weren’t crowned with a trophy-lifting moment at dusk in Southern California on the opening night of a new year.

The problem with the final years of the Fry era in Iowa City — a very good problem for any program, but a problem nonetheless — is that the world-class assistants from the 1981 team tried to leave their own mark on the world.

Bill Snyder changed Kansas State forever. Alvarez did the same at Wisconsin. McCarney became a very solid coach at Iowa State. Then there’s that Ferentz fella. Where’d he go?

Players under Fry added to the quality of the Texan’s fabled coaching tree. Bob Stoops (a member of the 1981 Big Ten champions), Mike Stoops, Chuck Long, and Bret Bielema all played at Iowa and then worked for their mentor as assistants. They also left the nest when it was time to climb the coaching ladder. Snyder took the Stoopses with him to Kansas State. Bielema joined Alvarez at Wisconsin and then took over as the Boss Badger.

Fry could not replenish the resources he had on his staff. He also got old as a coach (a happy problem Iowa fans of yesteryear wished had occurred with Evashevski).

A change needed to be made. To whom would the torch be passed?

Ferentz — who joined Iowa as a coach when the program took off in 1981 — answered the call.

Given his big break in the profession, Ferentz took his lumps in his first two seasons, but in year three, he went 7-5. Season four was a spectacular success, as Iowa ran the table in the Big Ten en route to an 11-1 regular season. Iowa didn’t go to the Rose Bowl, however, for two reasons: First, Ohio State shared the Big Ten title with the Hawkeyes and was slotted into the national championship game (the 2003 Fiesta Bowl). Second, USC — in second place in the Pac-10 that season — was good enough to get an at-large spot in the Bowl Championship Series.

The reshuffling of the bowl deck — with the Rose Bowl no longer locked into its Big Ten-Pac-10 format — sent Iowa to the Orange Bowl to face USC. A familiar dynamic awaited: A Pac-10 team with ample speed ran the Hawkeyes out of Miami. It was the other coast for a New Year’s bowl, but the same scenario as those Hayden Fry Rose Bowls had unfolded. It was as though Iowa lost a fourth Rose Bowl; it came in Orange-colored viewfinders.

Ferentz led Iowa to three double-digit-win seasons from 2002 through 2004. He later won the Orange Bowl, capturing the 2010 edition against Georgia Tech. After five underwhelming seasons, it seemed that Ferentz — like Mark Richt, Frank Beamer, and Bob Stoops (a former colleague under Fry at Iowa) — had run out of steam as a coach.

Yet, here are the former Fry assistants — Ferentz and Stoops — savoring their return to the pinnacle at the end of 2015.

While Stoops prepares for his College Football Playoff semifinal with Oklahoma, Ferentz is on a mission whose significance is almost as profound. Having led Iowa back to the oasis of the Rose Bowl for the first time in a long time — recreating the 1981 memory he also helped shape — Ferentz now gets his chance to chase away his Pac-12 demon. He gets a chance to lift a Rose Bowl trophy as night falls in the Arroyo Seco. He gets a chance to do something no Iowa coach has done in 57 years.

*

Before the 102nd Rose Bowl starts, Iowa fans of today will feel the way a previous generation did on the afternoon of January 1, 1982. The Hawkeyes, removed from the Rose Bowl far longer than anyone wanted, finally broke through and put an end to decades of waiting. The trick now is to leave one of college football’s most fabled fields with helmets held aloft, in possession of the victories attained in the 1950s but missed in the 1980s and 1991.

Can Iowa complete its present and draw a circle with its past? The mere reality that the Hawkeyes get a chance to make peace with their history is something which should inspire all Iowans as their team prepares for its big moment against Stanford.