Has it been 20 full years since the Final Four was last played in a conventional arena?

Does it feel longer or shorter since that moment passed through our lives?

The American sports fan has become so conditioned to expect a Final Four in a huge football dome that the days of “normal” Final Fours seem somewhat remote… even though the practice was more common than not in the 1980s.

The dome era of the Final Four actually arrived in multiple stages. The first Final Four in a big dome was the 1971 event in the Houston Astrodome. It only made sense that after the revolutionary 1968 regular season game between UCLA and Houston, John Wooden would win at least one of his championships in that game-changing dome made possible by Judge Roy Hofheinz.

Western Kentucky, Kansas, and Villanova joined champion UCLA at the 1971 Final Four in Houston’s Astrodome.

That 1971 Final Four was not the beginning of a trend; it was merely an event on an island. The next 10 Final Fours, from 1972 through 1981, were held in basketball arenas.

You’ll notice in the above photo of the Astrodome that the top deck was not filled. It was filled for the 1968 UCLA-Houston game, drawing a crowd of over 20,000 fans more than what the dome drew for the 1971 Final Four:

The UCLA-Houston seating layout and crowd in 1968, easily eclipsing what the 1971 Final Four delivered. This was the vision behind big-dome basketball.

The second wave of dome-era Final Four basketball began in 1982. This time, the idea stuck — not to the extent that the NCAA immediately abandoned conventional arenas, but enough to lead to more domed Final Fours and, in time, the permanent shift to football stadiums.

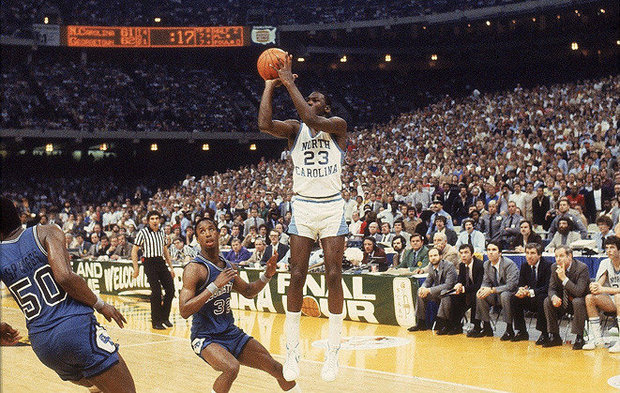

The NCAA hit the jackpot in 1982 by stuffing over 61,000 people into the Louisiana Superdome for an above-average Final Four with one of the all-time-great national championship games. The Georgetown-North Carolina classic was populated with multiple members of the Basketball Hall of Fame. Two of college basketball’s most important (not just accomplished) coaches led generationally great players — Patrick Ewing, James Worthy, and a developing freshman named Michael Jordan — into a dome which crackled with intensity. The game and the environment generated enough excitement that the moment’s immediacy was not lost in the size of the dome, which is what happened to an extent in Houston in 1971. The 1982 Final Four showed the NCAA a portal to the future in ways the Astrodome hadn’t been able to do.

It is coincidental but poetically fitting that the 20th anniversary of the last conventional-arena Final Four is marked by a Final Four in Houston… and not in the Astrodome, which has been turned into an ancient relic at this point.

You can see that every deck in the Superdome is filled for the 1982 Final Four, with the seating layout able to bring fans close to the court but with good sight lines. A problem in the current big-dome setup is that a lot of seats are roughly level with the court and don’t offer the tiered view you see with the bleachers set up in New Orleans 34 years ago. Many of the seats in a big dome — if they do have a better, more elevated sight line — are very distant from the court. The Superdome might be a 1970s stadium, but in many ways, it provides a basketball experience better than the modern venues. The Kingdome and the RCA Dome (both long since demolished) were similarly intimate in this regard, probably more than the Superdome, in fact.

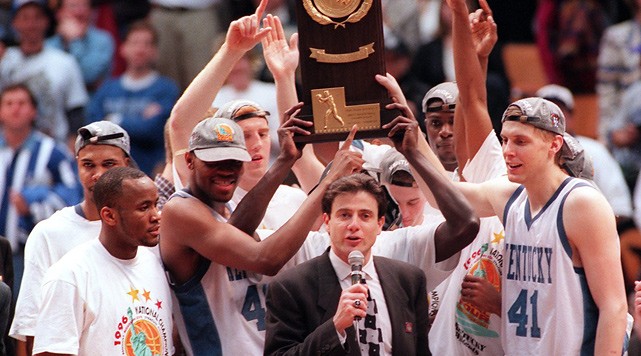

The success of the 1982 Final Four led to more domed Final Fours in 1984, 1987, 1989, 1991, 1992, 1993, and 1995. You can see that domes picked up a three-year streak and a four-in-five-year sequence; momentum was clearly gathering for domes as far as the NCAA was concerned, even if fans preferred the cozy feel of a normal basketball arena. Too much money was waiting to be made, so 1996 became the last hurrah for a regular building… and this was a very regular building: Continental Airlines Arena, formerly known as Brendan Byrne Arena.

More commonly: The Meadowlands.

The Final Four with a Statue of Liberty logo wasn’t even played in Madison Square Garden, the king of basketball arenas, all because of MSG’s longstanding relationship with the NIT.

The big issue raised by football domes is the familiarity of the shooters with the backdrop. We won’t make any sweeping statements about that topic. All we’ll note is that at the 1996 Final Four, the four teams — Mississippi State, Syracuse, Kentucky, and Massachusetts — shot reasonably well.

Here’s the first semifinal between Mississippi State and Syracuse:

The two national semifinals on Saturday (March 30, 1996) produced a 109-of-230 shooting line, 47.4 percent. The national title game two nights later created a 54-of-125 line, 43.2 percent. One could naturally point out that since legitimate college stars littered this Final Four — Erick Dampier of MSU, John Wallace of Syracuse, Antoine Walker and Ron Mercer of Kentucky, Marcus Camby of UMass — the skill level was such that shooting percentages would have been high regardless of the shooting backdrop. At any rate, the quality of basketball in this Final Four — while not transcendent as a whole — certainly rated as above average. The Kentucky-UMass national semifinal was a heavyweight battle which might not have met every last ounce of the runaway hype it received, but it came close, and generally did not disappoint.

The championship game between Syracuse and Kentucky — though pitting a 4 seed against the best team in the tournament — remained contentious and in doubt until the final minutes. Syracuse was still right there with a chance to win at the two-minute mark, but after rallying to trim a 13-point deficit midway through the second half, the Orange didn’t have anything left for a final push. Syracuse played a strong 38-minute game. Kentucky was able to run the full 40, and Rick Pitino won his first of two Commonwealth national titles. He’d win his second with Louisville, 17 years later in Atlanta.

The 1996 Final Four brought a “conventional” era to a close in college basketball. Will Saturday’s 2016 national semifinals make us yearn for the good old days?

If Buddy Hield hits 23 percent of his shots or Ryan Arcidiacono goes 0-for-8 from three-point land, you can count on a wave of columns pining for 1996 this Saturday night.