On Selection Sunday, Jim Boeheim received a gift from the NCAA Division I Men’s Basketball Committee.

He made very good use of it, leading the Syracuse Orange to the 2016 Final Four this weekend in Houston.

Boeheim also turned his own gift into a present for the very coach he’ll face in Saturday’s second national semifinal.

Funny how life works, right?

The always-chaotic 2015-2016 college basketball regular season begged for an absurd NCAA tournament, or at least, a few absurd events. No event was more preposterous than Syracuse’s magic carpet ride over the past two weekends.

The Orange limped into the Big Dance — fortunate that a bubble-game loss to Pittsburgh in the second round of the ACC Tournament didn’t result in an NIT bid — and then laid a smackdown on two first-weekend opponents before somehow escaping both Gonzaga and Virginia to make the Final Four.

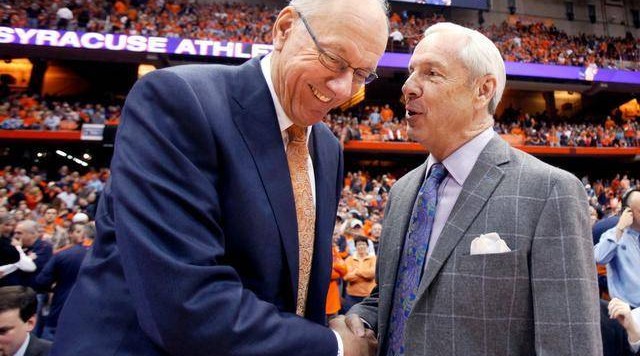

Jim Boeheim had guided two 4 seeds to the Final Four at Syracuse, in 1996 and 2013. His 2003 team was a 3 seed, but it needed the geographic proximity of Albany to beat top-seeded Oklahoma in the Elite Eight. In New Orleans, the Orange thrashed top-seeded Texas and then beat Kansas for Boeheim’s first national championship. The opposing coach that night in the Superdome: Roy Williams of Kansas, who made four Final Fours in Lawrence but never won a national title.

Remember the play which sealed Boeheim’s championship? Here it is:

Boeheim, you can see, has forged the best accomplishments of his career not with his best Syracuse teams (he’s never reached the Final Four as a 1 seed, only once as a 2 seed), but with incomplete teams which possessed a star (John Wallace in 1996, Carmelo Anthony in 2003) or a hot player (C.J. Fair in 2013, Malachi Richardson in 2016). The only time a loaded Boeheim team made the Final Four and lived up to its potential was in 1987, when Derrick Coleman and Rony Seikaly and Sherman Douglas and Howard Triche and Greg Monroe came within one basket — or one stop, or one pair of made free throws — of winning it all in New Orleans against Indiana.

It all seems upside-down, does it not? Boeheim’s best teams have generally fallen short of college basketball’s holy grail, while his less imposing teams have reeled off more (and better) March runs over the years. His least imposing NCAA tournament team just might have been this one, a 10 seed many people felt should have been a First Four team if it even belonged in the tournament at all. Yet, here it is in Houston, two wins from a national championship.

College basketball can be this way, in ways Boeheim knows all too well.

Roy Williams is just as aware of the capacity of this sport to troll and haunt its coaches into an unending stream of sleepless nights and decades-long what-ifs. Absurdist Theater 101.

We mentioned John Wallace earlier. There he is in the photo above, celebrating Syracuse’s win over Kansas in the 1996 West Regional final in Denver. Boeheim and Williams were brought together in an embrace of the absurd. Syracuse was given the gift of an 8-over-1 upset in the round of 32 when Tubby Smith and Georgia beat Gene Keady and Purdue. The Orange were in deep trouble against Georgia, but the last-second heroics of Wallace and Jason Cipolla rescued the Cuse and lifted the 4 seed to an overtime win. That was the first “carpet ride” Final Four of the Boeheim era, and it came at Williams’s expense.

The weird part of that 1996 season and NCAA tournament for Ol’ Roy is that those Jayhawks were the least polished of the four Kansas teams which threatened to make the Final Four from 1995 through 1998, the darkest period of his entire coaching career.

The 1996 team was the one team from ’95 through ’98 to not be a 1 seed — KU was a 2 seed 20 years ago. Yet, that Kansas group went deeper in March than the three 1 seeds Roy had in that four-year period. It handled third-seeded Arizona in the Sweet 16. Everything was on track for a Final Four appearance… until John Wallace came along. Syracuse, riding a wave in a manner similar to what would unfold at three points in the future (2003, 2013, 2016), walked away with the Final Four ticket. Roy was left outside the candy store in the Elite Eight.

March. It is a cruel beast, and the cruelty comes from its utter lack of predictability.

Consider just a few other upside-down twists from the past 35 years of the NCAA tournament and Final Four:

* Virginia didn’t make the Final Four when Ralph Sampson was an upperclassman in 1982 and 1983, but after he left, in 1984, the Cavaliers returned to the Final Four as a 7 seed… and very nearly beat Hakeem Olajuwon and Houston in an overtime national semifinal.

* Lute Olson made four Final Fours at Arizona, but the one team which won the national title was a 4 seed which struggled in the first weekend of the tournament and later needed overtime to beat 10th-seeded Providence in the Elite Eight. The next year, returning all of his key starters, Olson watch his top-seeded team — one of two favorites to win the national title (with North Carolina) — play its worst game in the Elite Eight, bombing out in a lopsided loss to third-seeded Utah.

* LSU’s Dale Brown guided an 11 seed to the Final Four in 1986, and a 10 seed within one basket of the Final Four in 1987. His teams with Shaquille O’Neal and Chris Jackson (later renamed Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf) never even got as far as the Sweet 16.

March. It often — and utterly — destroys logic and linear progressions. Coaches who have suffered many haunting and professionally scarring losses as high seeds have in many cases derived their greatest professional successes at the tail ends of supremely frustrating regular seasons.

Sure, Mike Krzyzewski doesn’t mess around when he’s a No. 1 seed. John Calipari and Rick Pitino have guided 1 seeds to the national title in the past five years. Billy Donovan, Bill Self, Gary Williams, and Tom Izzo have also led No. 1 seeds to the championship podium this century.

However, the larger point is plain: Being a 1 or 2 seed hardly guarantees success. Always being in position to make the Final Four is not the same as always (or almost always) getting there. Just ask Bill Self about this one, not just Williams.

The one bad game from the team as a whole; the one cold shooting day from your star (Perry Ellis last Saturday against Villanova); the one huge missed foul shot, especially on the front end of a 1-and-1; the one career day by the opposing point guard — all it takes is one of these plot twists to reduce a season to rubble.

Such is the excitement — but also the vicious and immediate finality — of a one-and-done knockout tournament. At Kansas, Roy Williams had to live with that reality far more often than he ever hoped to.

In the 2005 Final Four in St. Louis (above), Williams began to leave behind his tortured past at Kansas, where he led only one top seed to the Final Four (in 2002). His first great North Carolina team was a No. 1 seed. It proceeded to roll through Michigan State and survive Illinois for Williams’s first national championship. In 2008, North Carolina again made the Final Four as a No. 1 seed. In 2009, Williams won a second national championship in Chapel Hill, doing so as a 1 seed.

In 2012, UNC carried a top seed into the tournament once more, but as opposed to losing because of bad performances from players, this particular group fell short of the Final Four because star point guard Kendall Marshall got injured in the round of 32 against Creighton. Williams was unlucky, but he was unlucky because of an obvious deficit on his roster, not a coaching mistake or the simple unfolding of in-game actions.

Now, four years later — once again with a top-seeded team capable of greatness — Williams has successfully returned to the Final Four with North Carolina. He has become what he never did become at Kansas: the man who can ride thoroughbreds to the winner’s circle. The 2016 Tar Heels’ romp to the Final Four might have seemed to be easy, but the Roy Williams Kansas years — soaked in the very same absurdity manifested by Jim Boeheim’s mad dash to glory this season — powerfully indicate that nothing about a national title journey is easy.

Has Williams possessed a lot of talent on his current roster? Sure he has. Yet, other coaches had plenty of talent, too, and they didn’t get the breaks when they needed them. Only Williams guided a top-seeded team to the Final Four this season. Tony Bennett of Virginia, Dana Altman of Oregon, and Bill Self of Kansas all fell one win short. Bennett in particular has to be wondering when his Final Four day will come. He had the superior team — with a 15-point lead midway through the second half — and is still waiting for his first Final Four as a coach.

When you realize how hard it is to make just one Final Four — due to the crazy things which can abruptly take place in a sport played by 19- and 20-year-old men — the idea that there’s nothing special in guiding a 1 seed to the Final Four becomes exposed as a very deficient, even ignorant, statement.

“Well of course he got to the Final Four — his team was a 1 seed with the most talent. Nothing special about that, right?”

Well, if it was that easy, where are all the other 1 seeds, and where’s Michigan State, a team many felt should have been a 1 seed? These things should never be taken for granted… right?

If Jim Boeheim can make the Final Four with a 10 seed, whereas so many finer Syracuse teams left the Big Dance early, Roy Williams can get more credit for becoming at North Carolina what he always wanted to become — but never could — at Kansas: a man who makes the greatest use of his best teams.

That, in short, is Boeheim’s lasting gift to Roy Williams. Making the Final Four in a ridiculous way under odd circumstances is the best way to show the nation that making the Final Four as a 1 seed is no small feat.