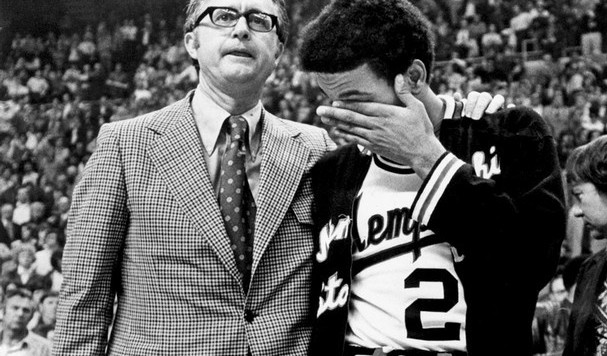

The story of Memphis basketball isn’t fully contained in the picture above, but a lot of the Tigers’ best moments flowed from the two men in that photo.

More instructively, the prestige and cachet of the Memphis job were built by those two individuals, so that future players and coaches could attempt to take the Tigers to an even higher level:

Yes, before John Calipari and Derrick Rose took Memphis to the national championship game in 2008, two trailblazers gave this program an identity — not necessarily as a fixture in the later rounds of the NCAA tournament, but certainly as a program which flourishes when a quality coach can take advantage of one of the more fertile recruiting areas in the country.

The coach in the black-and-white photo is Gene Bartow, who later started UAB athletics from scratch and led the Blazers’ newborn basketball program to the Elite Eight in a period of only five years. Before creating something entirely new at UAB, Bartow replaced John Wooden at UCLA and led the Bruins to the 1976 Final Four. Three years earlier, the moment in the photo came to life: Bartow guided Larry Finch — the dejected player standing next to him — and the rest of the 1973 Memphis State roster to the national championship game against Wooden, Bill Walton, and UCLA.

Memphis State had no chance in what was the first Monday night NCAA tournament national title game. Walton played the best national championship game of all time — then and now — hitting 21 of 22 shots for 44 points. There can be no shame in losing to an all-time player, an all-time coach, and an all-time sports dynasty at their shared height. Memphis basketball had arrived. What’s more is that even before that arrival on the big stage, the Tigers were coveted by a person who became one of the most centrally visible figures in college basketball over the past half-century.

The world of college basketball in 1970 was a very different one compared to what we know now. That year’s Final Four produced Jacksonville in the national championship game, and New Mexico State and Saint Bonaventure as national semifinalists. UCLA ruled the roost — just as it would three years later against Memphis State — but so much else about the sport would throw a curveball to fans who only view the sport through a 2016 lens.

Just one of many dozens of differences in the 1970 world of college basketball — relative to today — is that Wake Forest was not a bottom-rung program. The Demon Deacons were just eight years removed from a Final Four appearance. One of the men who led Wake to the 1962 Final Four was none other than a guard named Billy Packer. He had become an assistant on the Demon Deacons’ staff.

He wanted to jump to a program worthy of his coaching abilities.

Packer’s choice? Memphis State.

Bartow, however, beat him out for the job in 1970.

That marked the end of Packer’s coaching career… and led to the beginning, a few years later, of one of the longest careers in the history of network sports broadcasting, one which took Packer to 34 straight Final Fours from 1975 through 2008. That 2008 Final Four was, of course, the one Memphis could have — should have — won. Billy Packer’s career in and around college basketball is in many ways a reflection of how important the Memphis program is and has been since the early 1970s.

That’s not the end of the story, either.

Dana Kirk was a troubled soul, and he ran afoul of the NCAA (to a severe extent, it must be conceded). Nevertheless, the battles between his Memphis State teams and Denny Crum’s Louisville teams in the mid-1980s — such as the 1986 Metro Conference Tournament championship game, below — electrified college basketball:

In the early 1990s, Finch — having learned from Bartow and other mentors — became a credible coach in his own right. He guided Memphis to the Elite Eight before the Tigers lost to Cincinnati, another school which joined Memphis in the Metro Conference and then moved to the Great Midwest Conference before leaping to Conference USA and (now) The American.

The reality of being dragged through many different conferences in the course of realignment might be seen as a negative for Memphis, but in many ways, that progression only serves to underscore how durable the program and its brand actually are. The fact that Memphis made the national title game from Conference USA in 2008 — when no other program in the league offered much of any resistance — showed that Memphis could rise above its circumstances and become great on its own terms.

A great comparison to Memphis basketball is TCU football: The Horned Frogs were thrown around like a rag doll in terms of conference affiliation over the course of multiple decades. Here they stand today as a college football power, much as Memphis did under Calipari a decade ago. Sure, Memphis took a wrong turn under Josh Pastner, but as the program searches for a new head coach, only one verdict makes sense:

This is a job great coaches should want to have.

The story started with Packer and Bartow and the 1973 title game. It continued in the 1980s, when Memphis State was the only non-Big East program at the 1985 Final Four in Rupp Arena. The story developed in the 1990s and nearly reached the pinnacle of college basketball in 2008 in San Antonio — if only Derrick Rose had made a few more foul shots and Calipari had fouled before Mario Chalmers of Kansas released his thunderbolt of a three-point shot.

Great coaches succeed at Memphis. Great coaches have resources to use at Memphis. Great coaches need not worry about conference affiliation at Memphis.

Yet, there’s one more thing to emphasize when making the point that this is a big-time job in college basketball: In ways that don’t often exist at other schools around the country, Memphis is a job in which the local community deeply cares about the program.

For a great many schools, football is the main sport. For many other schools, football might not be the cultural center of campus life, but basketball success will not acquire a spiritual level of significance.

At Memphis, basketball success means more than success in any other sport… and not just because success in other sports means comparatively little. At Memphis, basketball success is hungered for with a passion few other schools can match. This might acquire the form of unrealistic expectations at times — or bitterness over Calipari’s departure in 2009, or delusional optimism about Pastner’s arrival as head coach — but just how different is that from any hoops-mad fan base?

It’s true that Gregg Marshall has already made a Final Four at Wichita State. Yet, if he’s thinking about an upward move in the coaching ranks, where would he go?

UCLA is probably the most realistic Cadillac job out there. Steve Alford could stumble next season, in which case that job would come open. Other than that, though, where are the options? Duke, Carolina, Michigan State, Kentucky, Louisville, Kansas, Villanova, Arizona, they’re all taken. Tom Crean has secured his hold on the Indiana job Marshall might have had a chance to get a year ago if the Hoosiers had spent the big bucks to engineer a buyout.

Are Memphis fans unrealistic? That’s a question for you to think about.

Are Memphis fans more unrealistic or unreasonable than UCLA fans? That’s a question which can be answered clearly: NO.

Moreover, if we’re comparing Memphis fans to UCLA fans, let’s acknowledge this much as well: If — for the sake of argument — you accept the premise that both are equally unrealistic, one fan base certainly cares a lot more than the other. A lot of sports options exist in Los Angeles, whereas Memphis faces the likely deconstruction of the Grit-and-Grind Grizzlies and is coping with football life in a post-Justin Fuente-and-Paxton-Lynch world.

Memphis basketball is The Show. UCLA basketball — for all the championships and tradition John Wooden brought to Westwood — largely lives on its past, not in the present tense.

If Gregg Marshall or any other hotshot coach wants to be great and become loved on a large scale — two things which any rational human person craves — Memphis basketball isn’t a bad choice at all.

It’s not Kentucky or Duke or Indiana.

And?

It’s a lot better than most other options.

It’s also a job that’s been coveted by smart basketball minds since 1970.

It’s a job which has produced Elite Eight teams or better in each of the previous four calendar decades, regardless of varying conference affiliations.

Memphis basketball? Great coaches — such as Gregg Marshall — should want to coach there.

That’s a statement which can be made with considerable confidence.