It’s beginning to be that time of year, sports fans.

Selection Sunday’s just 20 days away. You’re going to see this acronym a lot over the next three weeks: RPI.

The Ratings Percentage Index is not the only tool used by the NCAA Division I Men’s Basketball Committee, but it is one tool, and the fact that it is a tool should itself be concerning. RPIs don’t completely determine seeds, but they provide one of several measurements by which seeds are ultimately arrived at.

With each passing season, the more it becomes apparent that this system just isn’t good enough to be used in the war room in Indianapolis. Want to get a quick overview of why college basketball needs to say “RIP” to the RPI?

Let’s set the tone for the coming weeks by hitting on a few key points.

*

There are different ways to cook the RPI’s special sauce, and let’s acknowledge up front that while the RPI is an extremely deficient tool, coaches are not doing their jobs if they believe they have NCAA tournament-worthy teams but fail to schedule in a way that enhances their RPI. A perfect example last season was Utah, which scheduled one home-court cupcake after another instead of playing two road games against teams in the 75-150 range of the RPI, and a roadie against a top-25 RPI team. Had Utah scheduled better in three D-I games while also eschewing two non-D-I games, the Utes might have been able to squeeze into the First Four. At the very least, they probably would have been a “First Four Out” team instead of a team that had clearly been eliminated by Thursday afternoon of conference tournament week. Coaches should definitely know how to schedule to the RPI, and if they don’t, it’s their own fault.

That said, it’s absurd that we have to include discussion of RPI ratings in the science of bracketology, because we can see how badly the RPI serves college basketball at times.

*

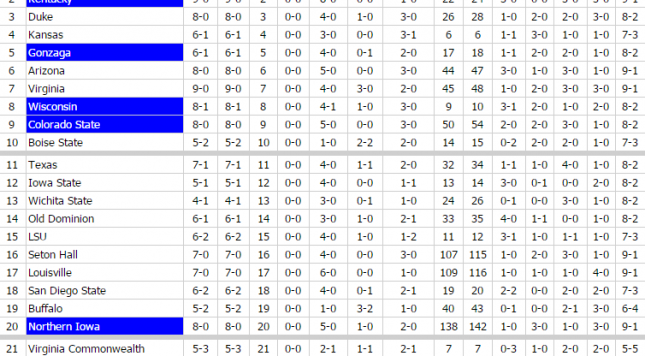

We’ll look at more “RPI case studies” during the week, but the foremost example of how this system is Regularly Punctured by Inaccuracies is Buffalo, which checks in at No. 42 on the newest list (games through Feb. 22).

Buffalo’s best non-conference win in terms of RPI is South Dakota State, at 88. The Bulls are an unremarkable 8-6 in the unremarkable Mid-American Conference, whose best teams — Central Michigan, Toledo, and Kent State — have not registered any significant landscape-changing non-conference wins. How in blazes are they 42nd, in the company of bubble teams such as Texas and solid NCAA tournament teams such as Ohio State?

They scheduled road games at Kentucky and Wisconsin.

Yes, Buffalo gave credible performances in those games — the Bulls lost by fewer than 20 points to each powerhouse team — but the fact remains that Buffalo lost by double digits to each side. Yet, if you replaced Kentucky and Wisconsin with teams whose RPIs are roughly equivalent to what Buffalo faces in the MAC on a daily basis, Buffalo would not be in this kind of discussion.

The Bulls are a 2015 example of how the RPI can easily be manipulated. They won’t make the NCAAs as an at-large team, though, so they’re harmless.

However, five years ago, the most conspicuous example of RPI manipulation occurred, and in that case, the team which knew how to cook the special sauce got rewarded.

*

The 2010 California Golden Bears should be studied whenever the RPIs flaws are brought up for discussion. The Golden Bears finished the season 22nd in the RPI. Again, the RPI is not the sole or even primary basis for seeding teams, so when you realize that a ranking of 22 is consistent with a 6 seed, the Bears’ No. 8 seeding in the 2010 NCAA Tournament seems fair on its face. Yet, when you look at what the Bears achieved in their season, they really shouldn’t have been in the tournament at all.

Here’s Cal’s combination of schedule and results from 2010. Here’s what you need to know about the Bears’ profile:

Syracuse, Ohio State, and Kansas were either No. 1 or No. 2 seeds in that year’s NCAA tournament. Cal played all three in road or neutral games, but lost to all of them.

The Bears did not win a single game against an at-large NCAA tournament team. They beat two teams that made the tournament as automatic bid-holders, UC-Santa Barbara and Washington. Regarding Washington, the Bears went 1-2 against the Huskies, having played them three times in Pac-12 play (the third meeting being in the conference tournament). The 2010 Pac-12 (then the Pac-10) would have had only one team in the NCAAs if Cal had beaten Washington in the tournament championship game. When Washington won that game, the Huskies snuck into the Big Dance as an 11 seed. Had they lost, they would not have made the cut. The Pac was extremely week that year, much as in 2012, when Washington — as the regular-season champion — did not make the NCAAs as an at-large team.

Everything about Cal’s achievements — which is to say, a pronounced lack of them — should have left the 2010 Golden Bears in the NIT. Yet, Cal got into the field as an 8 seed, which is not even close to the bubble. (It is reasonable to say that a 10 seed or worse is a bubble team on Selection Sunday. No team with an expected seed of 9 or better should be sweating when the brackets are about to be announced. Generally, 11 or 12 seeds are the best reflections of what bubble teams actually are.)

The point should be clear: The RPI rewards strength of schedule to the extent that it doesn’t often matter if you win games against the tough teams you schedule. Just play really rough road games against top teams, and presto! Huge RPI boost regardless of performance/result/quality!

It should be a point of emphasis that if you schedule a bunch of tough games, you have to win a reasonable percentage of them. This is why power-conference schools — which have so many more opportunities to play their way into the field compared to mid-majors — should not get the benefit of the doubt if they do what Cal did (or rather, failed to do) in 2010.

Few commentator-analysts have been better or more relentless on this issue than Seth Burn, who blogs about sports analytics and has tried to develop an adequate ratings system as a legitimate alternative to the RPI.

This Seth Burn post is a must-read in order to understand the RPI’s flaws in greater detail. Here’s a handy and informative companion piece, which is just as valuable.

*

There’s a lot more to be said about the RPI, and believe us at The Student Section when we tell you that we’ll say a lot more in the coming days.

Today, simply know that this tool is one that simply cannot be allowed to exist in its present form.

RIP, RPI — that’s something a lot of college basketball commentators want to be able to say in the very near future.